14th Sunday after Pentecost, Year B: But will God indeed Dwell on the Earth?

Peter Elliott

Hebrew scripture presents us with two ways the community worshipped God: tent and temple. From Moses until Solomon, the community traveled with the ark of the covenant, kept in a tent. Containing the tablets of the Ten Commandments, the ark kept the community mindful that God was with them on the journey. It reminded them too of how to live in a community formed, they believed, by the true and living God. It reminded them of boundaries of human behaviour: like keeping sabbath, respecting elders, eschewing violence, and to keep a check on our human proclivity to desire/covet more. While, on first glance, the building of a temple would seem to distance a community from their experience of the earth, Solomon’s temple was designed to celebrate the creation story found in Genesis 1—a journey into the temple was to remind worshippers of how the earth is God’s sacred creation. Psalm 84 celebrates the annual pilgrimage through earth’s terrains to be with the community at worship in the temple. The author of the letter to the Ephesians takes and subverts rhetoric from the empire’s military to remind the Christian community that their ministry takes place in the context of strong opposition. And the gospel reading concludes a 5-week journey through the bread of life discourse in John 6—by pointing to the physical world it resists being spiritualized.

Commentary

1 Kings 8:(1,6,10-11), 22-30, 41-43: Solomon's prayer at the temple dedication

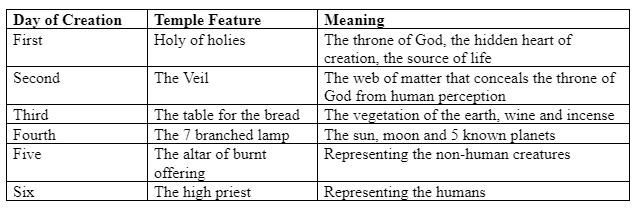

The reading from 1 Kings describes the dedication of King Solomon’s temple. The ark of the covenant is placed in the inner sanctuary’s most holy place, what was known as the Holy of holies. While it might seem that the building of a temple moves the worship of God from nature, in fact, the symbolism of the temple’s design represented the creation such that a journey into the temple was a journey into the life of God the creator of heaven and earth. In her book Temple Theology: An Introduction (London: SPCK, 2004) author Margaret Barker describes how the various features of temple worship replicated the six days of creation found in Genesis 1 (the Seventh Day, the Sabbath is God’s great gift, the pinnacle of creation, and the main point of the whole creation story)

This account of the dedication of the temple begins in the Holy of holies when the priests bring the ark of the covenant into the holiest space within the temple. Within the ark is contained the tablets given to Moses that inform how a community is to live its life. In Hebrew scripture, God’s concern is for how life is lived in community, summarized in the commandments. The source of just community living is found in relationship to the true and living God.

As soon as the ark is placed in the holiest place, the glory of the Lord fills the temple, a sign of God’s blessing not simply on the temple but on the enterprise of seeking to live in justice and peace on the land.

A veil between the Holy of holies and the table for bread represents how matter distinguishes the earth community from the divine presence. Solomon’s prayer is offered, most likely, at the table for the bread. Christians will, of course, immediately connect this table with Jesus last supper but it’s important to honour the Hebrew tradition in its own integrity without immediately “Christianizing” it. The table for the bread brings the vegetation of the earth into a central place within the temple, honouring the earth itself and its capacity to sustain life. From this space, Solomon’s prayer addresses three issues:

Honouring the God of Israel as the author of creation and the giver of the covenant.

The rightful succession of Solomon to the throne, paying due tribute to his father King David.

Asking that God bless the temple with divine presence and hear prayers of the faithful granting forgiveness.

But then, in a fascinating and perhaps unexpected moment, the King also asks that foreigners will be welcome in the temple, so that they too might experience the presence of the divine within it. This is consistent with commandment found (among other places) in the book Leviticus: "When an alien lives with you in your land, do not mistreat him. The stranger who lives as a foreigner with you shall be to you as the native-born among you, and you shall love him as yourself; for you lived as foreigners in the land of Egypt.” (Leviticus 19: 33-34)

The temple, in its symbolic representation of the Genesis creation story, far from taking the faithful away from the land connects them more deeply with the understanding that earthly life is lived within a divinely created space. In addition, it not only gives honour to the land but celebrates an ethic of inclusivity that understands that the universality of the love and justice of God.

King Solomon rhetorically asks, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” For him and the temple project the answer was “yes—through the temple which reminds us that the created order is from God; and God lives through the community God has formed especially as they seek justice, do kindness and walk humbly on the earth.

-

This beautiful Psalm is both within Judaism and Christianity. Scholar Walter Brueggemann, offers three categories of Psalms that correspond with three seasons of life that humans experience:

a place of orientation, in which everything makes sense.

a place of disorientation, in which we feel we have sunk into the pit; and

a place of re-orientation, in which we realize that God has lifted us up and we are in a new place full of gratitude and awareness.

Professor Brueggemann locates Psalm 84 squarely within the third category of re-orientation. This is because the writer of the Psalm is already aware of how faithful pilgrims have responded to Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. Devout Jews made a yearly pilgrimage there three times a year. The temple becomes, as we saw in the first reading, a place where the sacredness of creation was celebrated in the symbolism of its architecture.

Pilgrimage through dangerous terrain accompanied the frequent journeys up to Jerusalem, and Brueggemann identifies a tension between the Temple as a place for “the practice of alternative imagination” and its role as “part of the urban-political-economic establishment.” At its best, the temple, as a place for the practice of alternative imagination roots its worshippers in the sacredness of creation, reminds them, as King Solomon’s prayer did, of the importance of hospitality to the stranger (read foreigner, immigrant, refugee).

And as a sign of how deeply the temple is connected to the creation story, this Psalm celebrates that swallows and sparrows have a safe space within the temple precincts—a sign of how all of creation is included in the temple. As a place of pilgrimage, a space that symbolizes the creation, a sign to all people of the presence of God, and even housing innocent creatures, the temple can be a place for the practice of alternative imagination. In a time of climate emergency, when we seek to re-orient our lives so that humans might walk more gently and responsibly on the earth, creating spaces that practice alternative imagination become more and more urgently needed. Pilgrimage into the wild spaces of earth can be instruments that enliven a reoriented imagination.

Psalm 84 responds to King Solomon’s question, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” by celebrating and encouraging times of pilgrimage through the land, towards the Temple where, once again, all could be reminded of the creation story and be renewed in the commandments that make for community.

-

Whether it was St Paul or one of his disciples, whoever wrote the letter to the Ephesians was familiar with a form of speech called peroratio. This was a rhetorical style used by Roman generals to stir up the troops. The author of this section subverts this rhetoric to encourage the community of Jesus followers to be active, not passive in their ministries. In a time of increased violence and warfare, this text needs to be approached gingerly. In what ways can interpreters take the theme of activism and translate the military language in a way that, like the author of this text sought, inspire deep commitment.

The text begins with a reminder that the struggles of the time (then and now) are not so much against human agency but against ‘the cosmic powers of the present, the spiritual forces of evil.’ Walter Wink in Naming the Powers (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984) writes,

“... it is clear that we contend not against human beings as sun (“flesh and blood”) but against the legitimations, seats of authority, hierarchical systems, ideological justifications, and punitive sanctions which their human incumbents exercise and which transcend these incumbents in both time and power...For the institution will guarantee the replacement of this person with another virtually the same, who despite persona preferences will replicate the decisions made by a whole string of predecessors...It is this suprahuman quality which accounts for the apparent “heavenly,” bigger than life, quasi-eternal character of the Powers.”

It’s helpful that advocates for climate justice be reminded that the roots of the ecological crisis lie not with one person or one idea, but in a complex intersection of interests, appetites, and profit motives that have combined to create an unsustainable system that is making this planet less and less habitable for humans and other earth creatures. Justice work is holy because it seeks to address not just political realities but spiritual powers as well. The inculcation of an alternative imagination requires effective communication so that the tireless work of justice making can be engaged with energy and liveliness.

This Ephesians text provides a model for subverting imagery in service of the gospel. What would it be like to, for example, de-militarize this text by referring not to armour but to clothing. Addressing, for example, issues raised by ‘fast fashion’ (https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/what-is-fast-fashion/) opens up how the production of textiles impacts the environment, contributing to landfills with garments worn only once or twice, and its role in exploiting workers many of whom receive subsistence wages for long hard hours of labour. Thinking about the clothes we wear, and seeing garments as symbolic of our desire for greater justice not only for the people of the earth but for the earth itself could subvert the militarism extant within the text.

This text often comes near the end of summer in the northern hemisphere when many are focussed on the beginning of an autumn season of school and activity with its attendant impulse to get new clothing. What would it be like to use this text as an invitation to make the daily action of putting on clothes to be a prayerful way to prepare for the work of justice making? So, when you put on your—

· belt—remember to tell the truth

· shirt—to cover yourself with a desire for justice (righteousness)

· shoes/sandals—to walk in a peaceful way

· shield? —could this be a backpack or briefcase where you carry a symbol of faith—a cross, a Bible, an icon?

· hat/helmet—bike helmets, sun hats, ballcaps—when we don them, remember that salvation/healing is for the whole creation.

· sword—ok, this is harder to interpret—how about thinking that in the same way that a sword is for protection—as you get dressed, pray that the Holy Spirit might surround you, protect you as you go about the work of justice-making. The protection prayer can be a resource for daily devotions: “The light of God surrounds me; The love of God enfolds me; The power of God protects me; The presence of God watches over me.”

This section of Ephesians would respond to King Solomon’s question, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” by pointing to how the followers of Jesus are equipped to be the agents of God’s mission in the world.

-

The Year B period of dwelling in the 6th chapter of John’s gospel for five weeks concludes today thus offering an occasion to look at the whole chapter. A quick review will help contextualize these last 3 verses:

This sixth chapter begins with John’s telling of the miraculous feeding. John makes explicit a link between this miraculous feeding and the gift of manna in the wilderness as described in Exodus. As if to ensure that readers don’t miss the point, the author of John brackets the story of the feeding of the 5000 with a trip across the Sea of Galilee—connecting this with the liberation of the enslaved Hebrews from Egypt.

On the other side of the Sea, Jesus makes explicit the connection between manna and the miraculous feeding, identifying with the bread in the first of the great “I am” statements (I am bread, light, gate, shepherd, road, resurrection, vine). The “I am” is, of course, not Jesus being ego-centric but rather invoking the tetragrammaton—the holy name that cannot be named, the name Moses heard the divine voice speak from the burning bush “I am who I am.”In the “I am” statements Jesus identity as ‘the word made flesh’ is affirmed.

The 4th gospel was offensive to some in the crowd as John describes. Throughout the chapter, the ‘people’ are murmuring and complaining, again the author is remembering the complaining of the children of Israel in the wilderness. Jesus words become more and more offensive, especially when, in an almost off handed way, the author writes, “He said these things while he was teaching in a synagogue at Capernaum.” Really? No wonder people were offended! This conflict likely reflects the sitz in leben of the Johannine community, as Biblical scholar Raymond E. Brown suggests in his Anchor Bible commentary. Brown argues that the Fourth Gospel doesn't just report the life and Resurrection of Jesus: it's also an allegory for the experiences of the Johannine Community itself. Brown thinks the Johannine Community were Jewish Christians who stayed as part of the Jewish religion right through to the 70s CE. They had a heroic leader (the Beloved Disciple) and believed Jesus to be the Messiah, which brought them into conflict with other Jews. However, after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, Judaism reorganised itself. In 90 CE, the Council of Jamnia set out new rules for Jewish worship and took steps to expel the minim (heretics, which included Christians). The Johannine Christians were expelled from the Synagogues and found themselves friendless and despised. They were in danger too, because if they refused to worship the Roman gods (and the Roman Emperor) they could be arrested and executed. Brown thinks some of them were executed and this produced bitter feelings towards their former Jewish friends. Throughout John 6 you can glimpse the dynamics of this growing antipathy.

Three ideas can be of assistance in approaching this text. The Gospel of John does not include a narrative of the institution of the Eucharist at the last supper, John 6 offers a spirituality of the Eucharist; its sometime graphic description of ‘eating flesh and drinking blood’

1. The Jesus in John’s gospel, always the Incarnate Word, seems to be going out of his way to inhibit a desire to spiritualize his words. When one eats the bread of heaven, one is changed because you are what you eat. The very act of eating absorbs the energy of the food into our very selves. The bread the true bread that comes down from heaven is life giving—new life, abundant, justice seeking life. The bread and wine of the Eucharist are to intoxicate the receivers with the life of Jesus so that our lives and his are cojoined to become the living presence of the divine on the earth. In her groundbreaking book Poetics of the Flesh Maya Rivera writes,

“Jesus wants to transform—wants to save—more than our intellects, more than disembodied souls. His saving work was done in flesh, to save and redeem us as our whole bodily selves. Like with the manna in the desert, we may ask ourselves, “What is it?” But like manna, Christ’s body isn’t primarily given to us in order for us to understand it, but to consume it—and, having taken and eaten, to live.” (Rivera, Mayra. Poetics of the Flesh. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015).

2. Ronald Rolheiser describes how the elements of bread and wine connect both with Jesus suffering and the suffering of the earth:

“Out of what is bread made? Kernels of wheat that had to be crushed in their individuality to become something communal...like bread, wine has another side. Of what is wine made? Crushed grapes. Individual grapes are crushed, and their very blood becomes the substance out of which ferments this warm, festive drink.... It is helpful to keep this ambiguity in mind whenever we participate in the Eucharist. Bread and wine are held up ... precisely in their ambiguity. On the one hand they represent ... the goodness of this earth, the joy of human achievements, celebration, festivity, and all that is contained in that original blessing when, after the first creation, God looked at the earth and pronounced it good. But that's half of it. The Eucharist also holds up, in sacrifice, all that is being crushed, broken, and baked by violence.” In this time of climate change, the earth itself is being crushed, broken and quite literally baked by violence. (https://liturgy.sluhostedsites.org/18OrdB080424/reflections_rolheiser.html)

3. This lectionary passage concludes with Peter’s words, “Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life.” So as to not spiritualize, it’s important to note the meaning of the words eternal life. What does ‘eternal life’ mean? We hear this and our minds can go immediately to the afterlife. Many Christians think that the church exists for of cosmic life insurance—that if you, believe then you’ll go to heaven, and if you can’t believe you go to hell. People think of the afterlife, as somehow outside time, space and matter in a disembodied, timeless eternity. That is Plato, not the Bible. N.T. Wright’s book, How God Became King explores this idea. When, in John, Jesus speaks of ‘eternal life’ he uses words from an ancient Jewish belief about how time is divided. In this viewpoint, there are two “eons” the “Present age,” and the “age to come.” The “age to come”— which gets translated as ‘eternal life’ would arrive one day to bring God’s justice, peace, and healing to the world even as it toiled within the “present age.” There is hope, in other words, for this world, with all its injustice and cruelty, hunger and warfare. There is hope, there is a new age about to dawn. So, you can hear this verse this way: “Very truly I tell you, whoever believes has a part in the age to come.”

John’s gospel would respond to King Solomon’s question, “But will God indeed dwell on the earth?” with a resounding affirmation of YES—through the community in which the living Word resides in a mutual indwelling.

Teaching and Preaching Ideas

Since only 1 Kings and the Psalm are thematically related, the preacher’s first decision is where to focus.

Sunday Pilgrimage

If on 1 Kings and the Psalm, one could talk about the pilgrimage each person makes each Sunday to attend the liturgy. You could invite them to think about the land that they travel through, where are the pools of water? In what watersheds do they live? How does their experience of the church’s life enliven their understanding of the reality of the sacredness of all creation?

Fast Fashion

If preaching on Ephesians, consider exploring fast fashion, encouraging folks to think about the ways that the consumer culture entrances us with ‘back to school’ sales. Offer a meditation on clothes as ways to remember the call to discipleship.

How the Eucharist links us to the Earth

If the preacher chooses to focus on the bread of life discourse, it is a time to consider how the Eucharist links us to the earth—resisting spiritualizing the text and thinking about the labour that brings bread to our tables, produced from the grains that have been gathered, pummelled and formed into food.

Sources and Resources

Barker, Margaret. Temple Theology: An Introduction (London: SPCK, 2004)

Raymond E. Brown. The Gospel According to John Anchor Bible Commentary.

Brueggemann, Walter. Spirituality of the Psalms. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002

Rivera, Mayra. Poetics of the Flesh. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015

Rolheiser, Ronald “Bread and Wine” https://liturgy.sluhostedsites.org/18OrdB080424/reflections_rolheiser.html

Stanton, Audrey, “What is Fast Fashion Anyway?” https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/what-is-fast-fashion/

Wink, Walter Naming the Powers (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984)

Wright, N.T. How God Became King: The Forgotten Story of the Gospels. HarperOne, 2016.

Contributor Bio

Peter Elliott is a priest in the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster. In 2019, he retired after serving as Dean of Christ Church Cathedral on the unceded and traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Peter currently works as a consultant and coach in private practice, is adjunct faculty at Vancouver School of Theology and is the co-host of the podcast the Gospel of Musical Theatre. https://gospelofmt.podbean.com

Image

Abandoned Textile Factory interior by DarkDay