17th Sunday After Pentecost, Year B: Wisdom Cries Out in Many Voices

Kateri Boucher

This week, we are called to listen to the Wisdom crying out to us with counsel and warning… to resist the lies of human supremacy that have been handed down to us through the Biblical tradition… And to remember that surrendering our egos will ultimately allow us to join the great abundant ecosystem and Kingdom of God.

Commentary

-

This passage opens up with Wisdom crying out in “the streets,” “the squares,” “the busiest corner,” and at “the entrance of the city gates” (verses 20-21). In other words, Wisdom is crying out in the centers of Empire – the places where humans are most populated and least likely to be living in right relationship with each other and the land.

It’s presumably these city-dwellers and city-goers, then, who Wisdom refers to as “simple ones” and “fools” (verse 22). This reverses the dominant idea (then as now) that those who lived in the city were more complex, educated, and “civilized,” as opposed to the stereotypically “simple folk” who lived subsistence lives in relationship with the land.

Wisdom makes clear that she has offered herself to these city-dwellers time and time again, but that her counsel has not been received (verses 23-25). And she knows that consequences for this are inevitable. She doesn’t say if, but “when panic strikes you…” (verse 26). To demonstrate what this may look like, she evokes two wild and natural beings: storms and whirlwinds (verse 27).

Although the word “like” is used in both cases, the evocation of these beings may be more than just a metaphor. Activist-theologian Jim Perkinson refers to the storms of climate crisis as “water speak” – water calling out to us, responding to that which we (white, Western humans) have done to her and to the lands. Unfortunately, as we know, these storms and whirlwinds tend to disproportionately impact those of the Global Majority/ Global South. Those who have most forsaken Wisdom are not necessarily those who most immediately suffer the implications of our folly.

Because the people have not listened to Wisdom, she gives a warning: “Therefore they shall eat the fruit of their way/ and be sated with their own devices” (verse 31). This promise carries an ominous foreboding: Will the human or city-dwelling way actually offer us the fruits we need to survive? Wisdom seems to be saying, “Okay, you can go against my advice, but you’ll be on your own from here.” Today, as global capitalism runs rampant and farmlands are destroyed, hunger and famine are becoming more and more prevalent (including human-made famines being imposed in places like Gaza). How long can the fruit of “our way” – rather than the earth’s way – sustain us?

-

From the start, this psalm de-centers humans and re-centers divinity in the mysterious works of the universe. I imagine the psalmist gazing up at a glorious sunrise or sunset, proclaiming that the heavens “declare God’s glory” (verse 1).

Day and Night themselves are personified here, imagined to be telling tales and sharing knowledge with one another (verse 2). These verses resist the dominant assumption that humans have some kind of monopoly on coherent speech and communication. The psalmist makes clear that Day and Night are still able to share their messages even without what we would think of as words or voices (verses 3-4).

The Sun is also a primary character in this poem, personified as a “bridegroom” and “champion” who “runs about the heavens” (verses 5-6). Similar language can be found in St. Francis of Assisi’s “Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon,” which begins its praising of creation by focusing on the splendor of the Sun.

The laws of the Creator are said to be more desired than gold and sweeter than honey in the comb (verse 10). Both of these comparisons evoke the sun again – with its glinting gold and honey hues. (The ordering of these comparisons may be a subtle suggestion that, of the two of them, honey is in fact the more valuable).

It is only after all of this that humans are brought into the picture – and here, we are not recognized for our dominance or splendor, but instead named as Creator’s humble “servant” (verse 11). The psalmist acknowledges human folly and faults (verse 12) and begins speaking in the first person, asking God for help. They ask specifically that God not let their sins “get dominion” over them – again, resisting the assumption of “human dominion” over the earth (verse 13).

It is this God – the Creator of the sky, the sun, day and night, gold and honey – who is named as the strength and redemption of humans (verse 14), and the one who ultimately who can offer us “wholeness” (13).

-

In contrast with this week’s Psalm selection, this Epistle features human domination front and center. James counsels his readers to take care with their speech, exemplifying this through the image of a horse with a bit in its mouth and bridle on its back, being made to “obey humans” (verse 3). He revisits this theme a few verses later, now claiming that indeed “every species of beast and bird, of reptile and sea creature, can be tamed and has been tamed by the human species” (verse 7).

This problematic language takes after Genesis 1, which asserts human’s “dominion” (radah) and right to “subdue” (kabash) all creatures of the sea and sky. For the last two millennia, Christians have used language like this to justify human supremacy and destruction of our more-than-human kin. Recent theologians have called for reframing this language with the lens of stewardship, responsibility, custodianship, and mutual care.

James also evokes the elements of air/wind and fire. He says that the tongue is like a small rudder directing a large ship (verses 4-5) and like a small fire that can set a great forest ablaze (verses 5-6). Interestingly, focusing on these elements in their natural contexts may trouble James’s intended point about the tongue’s singular power. In the case of the ship, it’s not just the rudder that makes a large ship move, but the great wind itself. In the case of the fire, it isn’t just the fire that spreads itself, but the forest that provides its tinder.

The passage closes with three more examples from the natural world: a spring, a fig tree, and salt water (verses 11-12). James points to each of these as examples of “natural laws” that govern the world and uses them to encourage humans to follow in their lead, by allowing only blessings to come through our mouths (verses 9-10).

-

The first part of this text revolves around a weighty question posed by Jesus to his disciples: “Who do people say that I am?” (verses 27-30). This is not just a question of mere title but one of identity. The importance of Jesus’s naming aligns with Indigenous traditions around the world, in which one’s name is a spiritual and communal identification, born out of deep listening to the land and the spirit world.

Jesus seems to accept Peter’s identifying him as the “Messiah” (verse 29), but he immediately goes on to refer to himself as “the Human One.” In doing so, Jesus centers his embodied, incarnate nature. In Say to This Mountain: Mark’s Story of Discipleship, Ched Myers et al. remind us that his identifying as the “Human One” connects him to “the persona who earlier challenged the debt system and restored the Sabbath tradition of Jubilee” (p. 101). They also point out that the name is “taken from the apocalyptic vision of Daniel 7,” which affirms Jesus’s “nonviolent power” amidst a culture of violence (p. 101).

Later, though, Jesus rebukes Peter for being too focused on the human aspect of things, not able to zoom out and see the bigger divine picture (verse 33).

When Jesus calls to the crowd, he invites any and all of those present to come after him (verse 34). He does not make any qualifications based on gender, trade, dis/ability status, or access to wealth. In a social context filled with qualifications like those, the absence of such would have made Jesus’s invitation all the more radical. In order to join this movement, one must only be willing to “deny themselves and take up their cross” (verse 34).

He explains: “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it” (verse 35). This paradox rests on two different understandings of what it would mean to “save one’s life.” In the first, Jesus seems to be referring to those who cling to their small, individual lives, and try to protect their own interests at all costs. In the second, Jesus seems to be referring to those who recognize themselves as part of a greater Big-L Life… as a body of Christ… as an ecosystem. In order to save the larger life, one must lose one’s small life.

Themes

Grandmother Wisdom

The personification of Wisdom (hokhmah) appears and shapeshifts throughout these readings.

In Proverbs, Wisdom appears as a prophet crying out in the streets, the squares, the “busiest corner,” and at the entrance of the city gates (verses 20-21). In other words, Wisdom is crying out in the centers of Empire – the places where humans are most populated and least likely to be living in right relationship with each other and the land. Wisdom makes clear that she has tried to reach the people, but that they are not listening, and will therefore suffer the consequences.

To demonstrate what this may look like, Wisdom evokes two wild and natural beings: storms and whirlwinds (verse 27). Although the word “like” is used in both cases, the evocation of these beings may be more than just a metaphor. Activist-theologian Jim Perkinson refers to the storms of climate crisis as “water speak” – water calling out to us, responding to that which we (white, Western humans) have done to her and to the lands. Unfortunately, as we know, these storms and whirlwinds tend to disproportionately impact those of the Global Majority/ Global South. Those who have most forsaken Wisdom are not necessarily those who most immediately suffer the implications of their folly.

Where do you hear Wisdom crying out today? Where might Wisdom be trying to reach you in your own life, in your community, or in your watershed? Do you feel that it is “too late” for Wisdom to reach you or humanity? What emotions does this passage evoke for you? Fear? Grief? Relief?

In today’s Psalm, rather than Wisdom calling out to humans, a human calls out to Wisdom. As the psalmist praises Creation, Wisdom appears in relation to God’s laws. It is these great laws that “make wise the simple” (verse 7). In this reading, Wisdom is framed as that which aligns with the natural laws that govern the earth and heavens. The psalmist acknowledges their own folly and faults (verse 12) and asks God for help in following the way of the law and Wisdom.

Where do you experience the Wisdom of the natural world? Which more-than-human kin in your watershed teach you how to live in alignment with the natural way of things? How might you call out to Wisdom as you ask for help in this time of climate crisis?

Wisdom shows up in today’s gospel too – through the person of Jesus. Activist theologian Jim Perkinson has noted that John names Jesus as the logos – usually translated as “the Word.” But beneath that translation is the Hebrew word hokhmah – a feminine word meaning Wisdom. The same word is used in Genesis 1: “In the beginning was hokhmah.”

Given this, Jim asks, might we consider Jesus to be Lady Wisdom in drag? Might we imagine Wisdom to be speaking through Jesus, counseling humans once again to surrender to the natural order of things, lest we face dire consequences?

In their sermon “Jesus, Rewilded,” Sheri Hostetler and Joanna Lawrence Shenk invite us into this imagining together. They write: “[Lady Wisdom] is among us, spinning her healing web of reconnection. She calls us to follow in her path because she is as alive in the lands on which we live, as she was in the ecosystems of 1st century Palestine. What humans and creatures is she speaking through today? What does she smell like? What does she feel like? Where does she stop us in our tracks with her beauty?”

Human Supremacy (As Remedied by Human Humility)

From Genesis to the Epistles, the Bible includes language that asserts humanity’s “dominion” and God-given right to “subdue” the rest of our creaturely kin.

In this week’s Epistle, James explicitly echoes this view, asserting that: “every species of beast and bird, of reptile and sea creature, can be tamed and has been tamed by the human species” (verse 7). For the last two millennia, Christians have used this kind of problematic language to justify human supremacy, destruction, and violence.

Did you grow up hearing this kind of language? What were you taught about humans’ relationship to the rest of Creation? How has this impacted the way that you move through the world? How might this be impacting your church community or denomination?

James claims that every species has been tamed by humans – which creatures might beg to differ? Where do you notice resistance to human domination by our more-than-human kin?

Luckily, the other readings offer us some alternatives to this human-supremacist view.

The Psalm begins with praising of the heavens, the sun, and the laws of the Creator. It is only after all of this that humans are brought into the picture – and here, we are not recognized for our dominance or splendor, but instead named as Creator’s humble “servant” (verse 11). The psalmist acknowledges human folly and faults (verse 12) and asks God for help. They ask specifically that God not let their sins “get dominion” over them – demonstrating that humanity too is not above being dominated (verse 13). This psalm reads like a prayer for humility amidst a human-supremacist world.

The late appearance of humans in this Psalm is representative of the fact that humans are, in fact, latecomers to this earthly scene. Thomas Berry writes in The Dream of the Earth, “We now experience ourselves as the latest arrivals, after some 15 billion years of universe history and after some 4.5 billion years of earth history. Here we are, born yesterday. We need to present ourselves to the planet as the planet presents itself to us, in an evocatory rather than a dominating relationship. There is need for a great courtesy toward the earth.”

Naomi Ortiz recognizes this too in her recent Rituals for Climate Change: A Crip Struggle for Ecojustice. She says, “I am young to the ecology of this land/ so many cacti elders, fifty to five hundred years wise/ embrace when nourishment arrives.”

This kind of long-time perspective allows us humans to right-size ourselves and be humbled in face of the Created world.

Proverbs, too, paints a picture of humans (at least city-dwelling folk) as “simple” and “foolish,” and threatened by the destruction of whirlwinds, storms, and calamity. This is hardly the image of an all-powerful species! Wisdom offers instead an image of humans at the mercy of Creation, in need of much external guidance and support.

These readings are more aligned with recent theologians who have questioned the human supremacy baked into dominant Christianity and instead proposed reframing this language with the lens of stewardship, responsibility, custodianship, and mutual care.

In the Earth Bible’s Principles of EcoJustice, the fifth principle is that of Mutual Custodianship. It states: “Earth is a balanced and diverse domain where responsible custodians can function as partners with, rather than rulers over, Earth to sustain its balance and a diverse Earth community.”

Some Indigenous traditions do believe that humans have a unique caretaking role in Creation. In an interview titled “Humans as a custodial species,” Aboriginal author Tyson Yunkaporta describes this view: “There’s a dreaming story in western Australia, they talk about there was a big meeting. Everything, all the trees, the plants, the animals and humans who were in there [...] at the moment of creation, had to decide who the carers for everything were going to be. [...] It went through each of the traits of each animal and the trees were like, ‘Well, we can’t move around.’ And the kangaroo came really close, apparently. But he just had these shitty little arms. And they weren’t quite going to do it, so it ended up being the human beings. They had that capacity.”

However we understand our custodial relationship, the fact of mutuality remains: we are recent arrivals in a brilliant, glorious Creation that we are deeply dependent on and ultimately responsible to.

From Ego-Self to Eco-Self

Today’s gospel passage features a radical assertion from Jesus: “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it” (verse 35).

This paradox rests on two different understandings of what it would mean to “save one’s life.” In the first, Jesus seems to be referring to those who cling to their small, individual lives, and try to protect their own interests at all costs. In the second, Jesus seems to be referring to those who recognize themselves as part of a greater Big-L Life… as a body of Christ… as an ecosystem.

In dominant Western culture today, many of us are taught to identify solely with our small-self – what philosopher Alan Watts calls “the skin-encapsulated ego.” Jesus’s counsel speaks directly into our world of self-oriented individualism, calling us to expand our sense of Self to save the larger Life that surrounds us.

Buddhist philosopher Joanna Macy writes about this as a move from the ego-self to the eco-self. To illustrate this, she tells a story about her friend john Seed, an Australian rainforest protector. Joanna asked him about how he deals with despair in his work, and john replied, “I try to remember that it's not me, john Seed, trying to protect the rainforest. Rather, I am part of the rainforest protecting itself. I am that part of the rainforest recently emerged into human thinking.”

This is the kind of expansive self that I hear Jesus calling his disciples to in this text.

Have you experienced this expanded sense of Self before? Do you understand other beings (human or non-human) as part of your wider Self? What would it mean to consider your watershed as your Self? How have or could you practice “losing your self” in service of the greater whole?

Unfortunately, the ethic of self-denial has also been used in harmful ways in the Christian tradition. In Say to This Mountain: Mark’s Story of Discipleship, Ched Myers, et al. clarify that the call to deny oneself is not meant to be “a negation of experience, selfhood, human rights, or physical integrity” (p. 106). Instead, they write, this call “challenges the self as the center of one’s universe. It calls us out of life centered in individualism and self-interest and into life according to God’s love” (p. 106).

Myers, et al. offer us questions for reflection in the wake of this passage: “Where now does Jesus call you to take up the cross and follow him? [...] What are the possible consequences of your following this path? What do you most fear? [...] Who is the community that is called to be with you on this path?” (p. 107)

In The Dream of the Earth, Thomas Berry offers an urgent encouragement to shift from the ego-self to the ego-self: “The time has now come, when we will listen or we will die. The time has come [...] to resist the impulse to control, to command, to force, to oppress, and to begin quite humbly to follow the guidance of the larger community on which all life depends. Our fulfillment is not in our isolated human grandeur, but in our intimacy with the larger earth community, for this is also the larger dimension of our being. Our human destiny is integral with the destiny of the earth.”

Resources

“Say to This Mountain:” Mark’s Story of Discipleship by Ched Myers, Marie Dennis, Joseph Nangle OFM, Cynthia Moe-Lobeda, and Stuart Taylor

World as Lover, World as Self by Joanna Macy

Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World by Tyson Yunkaporta

Rituals for Climate Change: A Crip Struggle for Ecojustice by Naomi Ortiz

The Dream of the Earth by Thomas Berry

“Humans as a Custodial Species” interview with Tyson Yunkaporta (Garland Magazine)

“Go Out in Joy: A litany for worship adapted from St. Francis’ ‘Canticle of the Sun’ and related Scripture texts” by Ken Sehested (RadicalDiscipleship.net)

“Wild Lectionary: Who Do We Say….” by Rev. Dr. Victoria Maria (RadicalDiscipleship.net).

“Sermon: Jesus as Lady Wisdom in Drag” by Joanna Lawrench Shenk (Mennos by the Bay)

“Sermon: Jesus, Rewilded,” by Sheri Hostetler and Joanna Lawrence Shenk (Mennos by the Bay)

“The Symbolic and the Real,” talk by Alan Watts (Alan Watts Organization)

Season of Creation 2024 Celebration Guide for Episcopal Parishes https://newcreationliturgies.org/seasonofcreation/

Bio

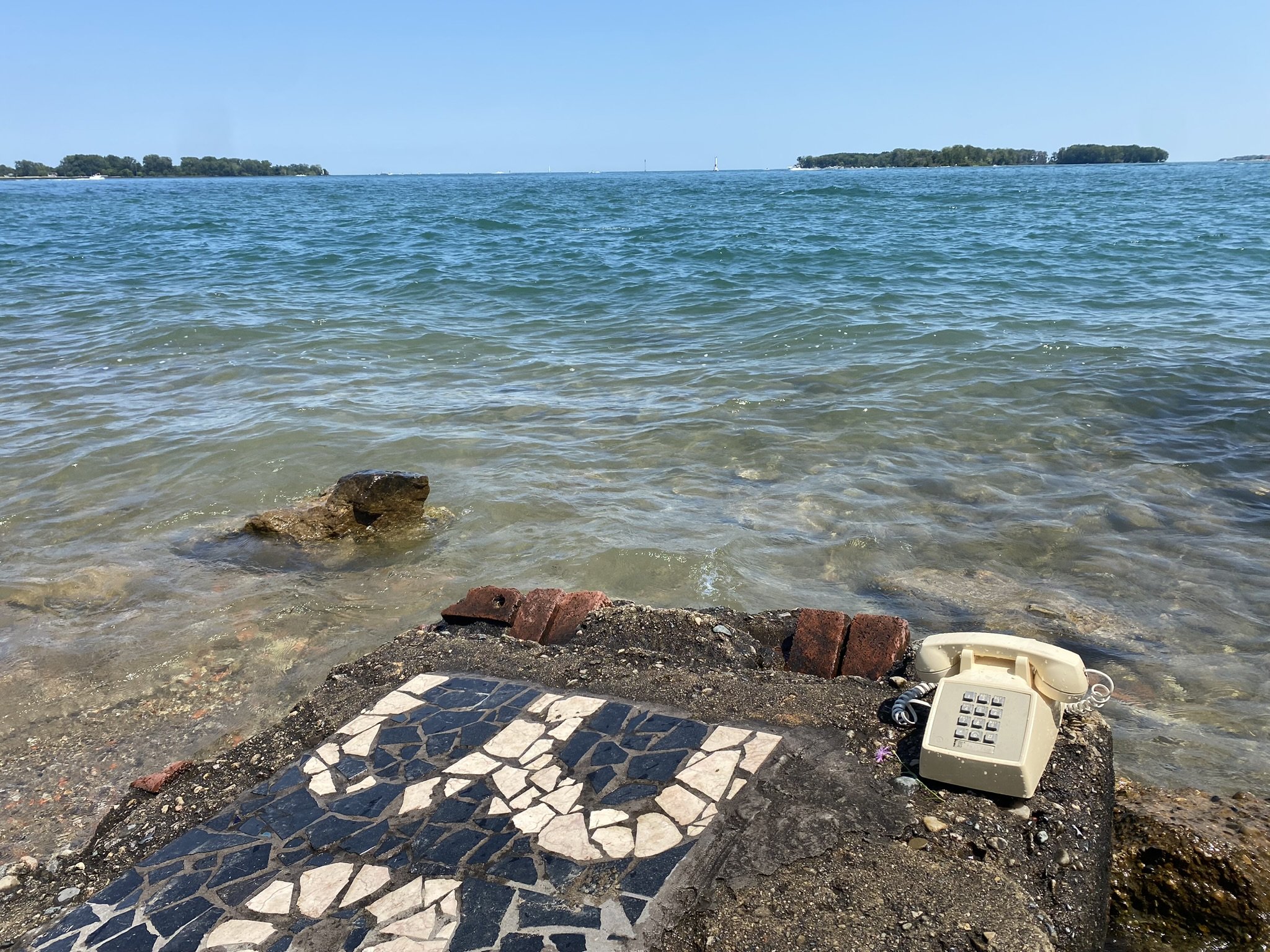

Kateri Boucher lives in Detroit/ Waawiyatanong – "where the water goes around." Her favorite part of the Detroit River watershed is Belle Isle (Wahnabezee), a 982-acre island in the middle of the river. She is the Ministries Coordinator at St. Peter's Episcopal Church and a Masters of Divinity Student at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities. She is the grateful caretaker of an opinionated tabby cat named Lucy.

Image

“Wisdom is Calling” (Belle Isle, Detroit, July 2024)

In the fore-ground a cream-colored push button telephone with handset, base and coil cord sits on a shore of brick, concrete and mosaic. The middle of the image is open water transitioning from brown to blue. The top fifth of the image is blue sky with two small treed islands on the horizon line.